Today we are going for a walk through the Milan’s city centre, with a brief introduction to its history and discovering some of its hidden pearls. Milan, unlike other famous Italian cities, does not shock you with its art, it has to be found. We are not going to see everything available, our objective is to enjoy a nice walk: choose the museums you like the most to visit, and in the worst case you can break it down in two days. A good suggestion is to start in the morning to get to the Duomo around lunchtime and find most of the attractions open. At the bottom information to book tickets and official websites can be found.

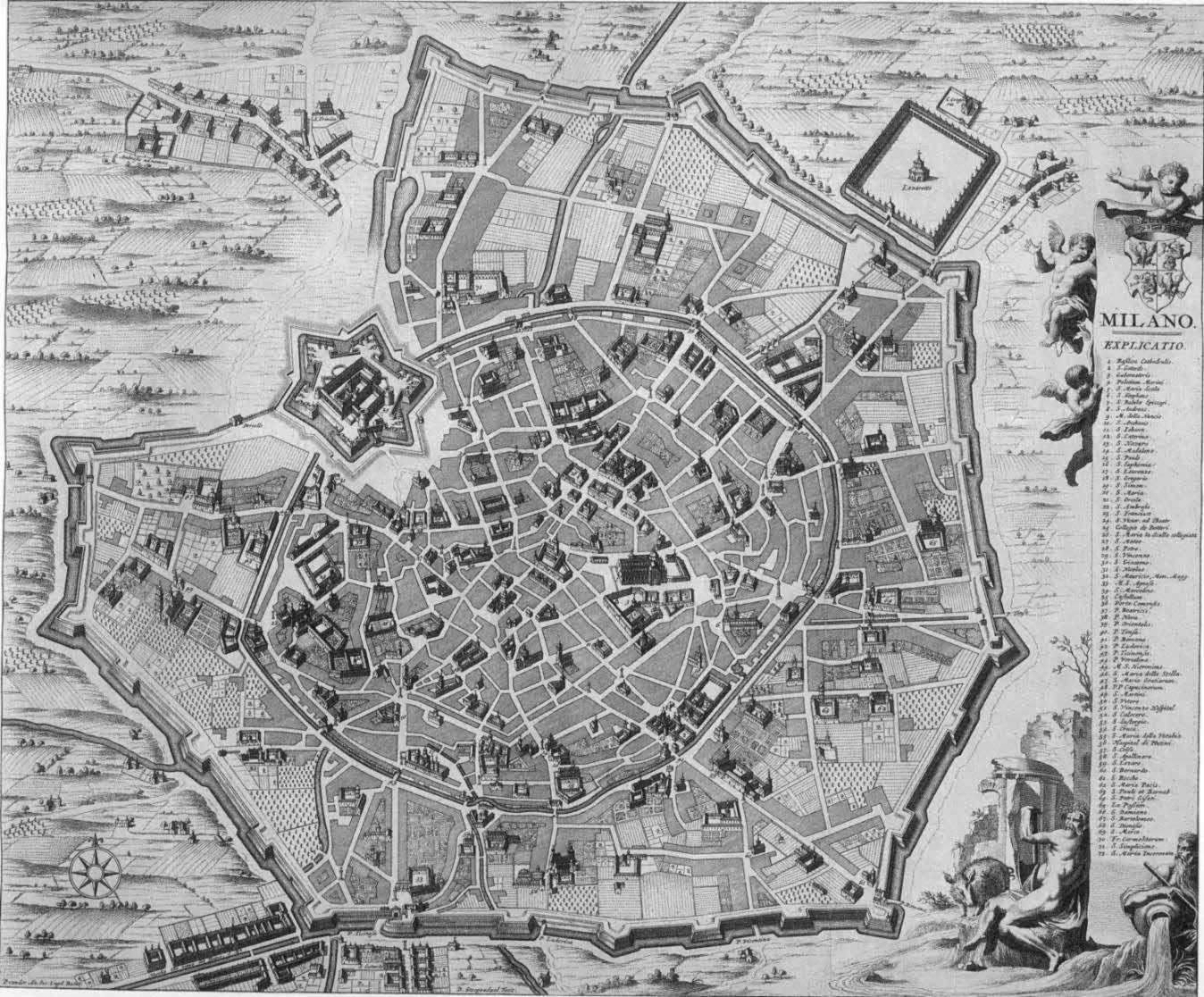

We start from Porta Venezia, an old access gate. The two toll booths on the side have been finalized in 1928, removing a temporary arch in between. Some of the statues are still damaged from the rebellion of the five days of Milan in 1848. This gate was used until the 18th century to defend and delimit the city, and was part of the Cerchia dei Bastioni. Few remains and gates is what is left of this Spanish walls, a massive bastion that spanned 11 km built between 1549 and 1561 and demolished after the second world war to make room for the middle ring road.

Milan in 1704, by Daniel Stoopendaal: the whole city is contained in the Spanish bastions.

We now enter the Indro Montanelli gardens, where the planetarium, dome-shaped building, and the natural history museum are located. Walking through the gardens many statues of many different styles can be admired, as well as Palazzo Dugnani, a 17th century palace decorated with stuccoes and frescoes of the mythological eighteenth-century Venetian school. In front there is a fountain, the only remains of the 1881 expo that was done in this very gardens, because it was the only space available within the city centre.

Stuccoes and frescoes of the mythological eighteenth-century Venetian school in Palazzo Dugnani.

At the other end the Archi di Porta Nuova can be seen, the only part left of the medieval walls. We’ll walk through the pedestrian passage on the left opened with the last renovation in 1861, and turn left in via della Spiga, one of the sides of the fashion square, the famous fashion design district in Milan. Shopping here is prohibitively expensive, but the shop windows are nice to look at.

On the way to Villa Necchi we pass by the intersection between via Senato and corso Venezia. In this very place was signed the manifesto of futurism, by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

A few more meters and we get to the villa: designed by Piero Portaluppi and commissioned by the Necchi and Campiglio families, wealthy enough to tell the engineer he had unlimited budget. The gardens are free and provide a nice resting point to sit down and enjoy the amazing scenery. The visit is definitely worth every euro spent (14€/5€), on the inside there are two main floors, 500 square meter each, the ground one for guests, the upper the private area. A spacious villa with splendid deco furnishings, all designed by Portaluppi and integrated by Tommaso Buzzi with a touch of Baroque style.

Front facade of Villa Necchi Campiglio.

Walking back via Mozart we shortly get to San Babila, a manifesto of fascist architecture from the thirties, which will be analysed later. At the beginning of the 20th century many buildings were demolished and space for this square was created. The name is derived from the Basilica di San Babila a first Romanesque style church consecrated in 9th century, which was rebuilt many times throughout history. Unfortunately little is left from the original church, but the last renovation from the end of the 19th century was faithful to the original. Inside, on the entrance wall, there is an organ, recently renovated through a donation, used to play concerts regularly.

Aerial view of Piazza San Babila.

We now walk down via Vittorio Emanuele II, first king of Italy, leading to the Duomo, the main cathedral. Immediately after leaving piazza San Babila there is a bronze scale model of the area and, on the right, the Basilica di San Carlo al Corso, a church that recalls the Pantheon in Rome, with a similar dome structure and columns. With a quick detour on the right side we can get to piazza del Liberty known for the former hotel in liberty style, now headquarters of an insurance.

We will get to the Duomo from the back side. After having a quick look at it a scaffolding will be evident, because since the beginning of its construction in 1387, the society La Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo is taking care of its construction, maintenance, and cleaning. The pink marble comes from Candoglia and is considered a prestigious material, it was transported through rivers and canals and since 1927 it may be used only for the Duomo.

The construction ended in 1932, “Long come la fabrica del Domm”, Milanese for “Long-lasting like the construction of the Duomo”, is the traditional way to criticise something never ending in Milan.

Until today it is rare to see it completely unscaffolded, it is constantly being repaired or cleaned.

On the very top of the cathedral there is a small golden statue of the Virgin Mary, Madunina in Milan’s dialect. Placed in 1774 at 108,5 meters height is, by law, on top of Milan. In the thirties, the fascist regime ratified that no higher building shall be built; for instance the Torre Velasca and the Torre Branca were capped respectively at 106 and 108m to conform to the law. Since 1954, the construction of the Pirelli skyscraper, three higher buildings were built, but on top of each a copy of the statue has been placed to respect the tradition. The roof and the Madunina are visitable, sadly not cheap and without any student reduction, but they provide an amazing bird’s eye view on the whole city centre (13€/9€).

Detail of the Madunina of the Duomo di Milano.

Before seeing the front facade, we turn right into via Santa Radegonda where we can stop for a proper lunch break or a quick snack. We can enjoy some typical Milanese food, like Spontini’s pizza (5€) or Luini’s panzerotto (3€, but get two), don’t be scared about potential queues, they move fast. To finish off a proper lunch break an espresso in the Lavazza café costs less than two euros; for and ice cream two different shops can be suggested: Cioccolati Italiani and Grom (3€-5€), worth trying.

Next stop: Piazza della Scala. The square inherits the name from the Teatro alla Scala, which in turn replaced the church of Santa Maria della Scala built in 1381 for Queen Beatrice della Scala. This theater, built in 1778, was originally used with disregard of today’s norms, people used to eat, drink, shout, play gambling games, and even have sex in the boxes. Since two hundred years this is no more the case and it is now worldwide famous for operas and ballets, that can be quite expensive. Tickets for the rehearsals are sometimes free or really cheap, especially for students, and can give a chance to see the insides. Its museum is visitable and will show part of the insides as well as a detailed insight on its interesting history (9€/6€).

Reproduction of the Scala theatre in the 19th century, unknown artist.

Exactly in front of the Scala is located Palazzo Marino, the city hall. It is said that on the gray walls of this building befalls a curse, an anonymous individual expressed all the hatred from a big chunk of the Milanese population towards the aggressive and repellent owner who built this building:

“The stone structure, built through theft, will either burn, fall into ruin or be brought away from another thief.”

Fortunately, this did not yet happen, but at the death of the owner in 1572 the building was seized by the Spanish, instead of being inherited. The interiors, decorated with magnificent stuccoes and frescoes, can be visited for free with a booking (check the official website for details).

Tapestry room, Palazzo Marino.

On the third side of the square the Banca Commerciale Italiana can be admired: it was the headquarters of the first merchant bank in Italy. The interiors are decorated with marble columns that sustain stained glasses and two majestic black background clocks. In this building since a few years there are the Gallerie d’Italia an exposition with art masterpieces from the 19th and 20th century (5€/3€). Though the vault no longer contains safe-deposit boxes, it has been re-adapted and safeguards something equally valuable: about 500 priceless paintings.

For the art enthusiasts close by there is the Poldi Pezzoli museum, that is also a great suggestion, as it offers a notable collection of Northern Italian and Flemish artists (10€/7€).

After admiring the square we can walk back to the Duomo, passing through the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. Built to celebrate the unification of the kingdom of Italy in 1861 it is nowadays a fancy shopping area. The roof is made in steel and glass, and close to the dome some frescoes can be seen. At the center, on the right side a bull, usually surrounded by people, represents Turin’s coat of arms: it is tradition, to mock Turin, to spin three times with the heel on the bull’s testicles brings good luck.

The front side of the Duomo is majestic: designed by many different artist throughout history, was the subject of many debates. Six huge pillars divide it in five parts, it is a mixture of different styles, even though the most is Gothic. A suggestion when going inside the Duomo (3€) is to bring a Binocular, to observe many of the capitols and far away stained glasses. Describing everything present in the Duomo would take more than some lines in a post, here only a couple of interesting facts will be listed.

The Madunina on top is not the only depiction of the Virgin Mary in the cathedral, there is one in the left sacristy, known as Madonna delle Rose, a fresco made in 1409; another portrayal is in the right presbytery, right by the entrance, named La Vergine dell’Aiuto. Little is known about the different last suppers in Milan: other than Leonardo da Vinci’s there is one on the south facade, in stained glass, 70 years older than the more famous one, alongside other five hidden in various churches and museums in the city.

Last supper stained glass in the Duomo.

Since 1933 on the duomo there is an ongoing boxing fight: two statues are fighting on a steeple from the fascist era. Only one was identified, the two champions are Primo Carnera and Erminio Spalla, the former is the first heavyweight category and the latter is the first Italian champion in the European tournament.

Statues of boxers on the Duomo, of the four only Primo Carnera and Erminio Spalla were identified, on the left side.

The Duomo has also many basements, some of which can be accessed (7€/3€, including access to the cathedral), some other that have been closed for hundred of years, like the underpass between the two side doors of the Duomo, disbanded because people were committing indecent acts and being loud during celebrations.

In Piazza del Duomo there is not only the Duomo, directly at its right there is the Royal palace, used throughout history by the rulers in Milan as a Palace to represent them officially in Milan. It is now mainly used as a temporary exhibition place, with many artists from the whole world for a couple of months at a time.

Another important building is the Museo del ‘900, about contemporary art (10€/8€). The first staircase is free and allows to see the The Fourth Estate, a divisionist masterpiece from 1901. It is really important to look for a second to the building itself, as it is a blatant example of fascist architecture in Milan. The typical features of this rationalist style are:

- imposing columns, often with a rectangular section, and plated in stone;

- linear and simple arches and architraves, with little decoration around windows;

- inscriptions and bas reliefs commemorating manual labor and the homeland.

The building itself, named Palazzo dell’Arengario, from arringa, Italian for speech, was used by Mussolini to hold his speeches and has all of the listed features.

Palazzo dell’Arengario, example of fascist architecture. The building on the left is the Museo del ‘900.

Looking beetwen this two buildings the Torre Velasca can be seen, an architectonic peculiarity with its “mushroom” shape, refusing the international consensus by trying to recall the shape of the Filarete tower we’ll see later in the Sforza castle.

After taking a couple of pictures and trying to avoid the pigeons, the black plague of Piazza del Duomo, we can keep on going towards Via Torino, where in a few hundred of meters we find a little, hidden, church on our left, Santa Maria Presso San Satiro.

Entering the church everything might appear normal but one detail is not apparent, if not going to the side: the chorus is almost flat, like a bas relief.

Due to space restrictions a full-fledged chorus was not possible and Donato Bramante managed to fit the illusion of one in only 97 cm thanks to perspective.

The path now splits in two different itineraries: if some energy is left, we will add the Colonne di San Lorenzo and later the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, if not just to the Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio and then directly to the Castello Sforzesco; on the map on the bottom the difference can be seen.

Other than being known for underage drinking, loud music, and public urination, the Colonne di San Lorenzo are the most known columns in Milan. Located between the Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore, the 16 Corinthian columns, all different in height, probably belonged to a pagan temple or thermal baths from the 2nd century and were moved here in the 6th century to make a solemn entrance to the important basilica. Many proposals to demolish them have been made throughout history, most notably in 1557 to honour the triumphal visit of Emperor Charles V.

San Lorenzo Columns and Basil in 1860.

Now, for the most important Basilica in Milan, we visit Sant’Ambrogio. The saint lived between 340 and 397 A.D. and was an Archbishop in Milan; he was an able diplomat and managed to settle many controversies between the church and emperor, while helping the population. For his abilities he became the patron saint of Milan, and he is celebrated on the 7th December. The church was built between 379 and 1099 A.D. and was consecrated in 386 A.D. Beware that this church closes for lunchtime, to avoid disappointment try to get here around 14:30/15:00.

Going through the main entrance we find a courtyard with a first Romanesque facade, and on the left, the real access to the church. Inside we can notice the statue of a bronze serpent on a pole, Nehushtan (or Nohestan), which God told Moses to erect to protect the Israelites who saw it from dying from the bites of the “fiery serpents” which God had sent to punish them. Let’s take a look at the dome: a golden mosaic named Sacello di San Vittore in Ciel d’Oro depicting San Vittore. Under the dome the altar, from the finished in 859 A.D. wooden and gold-plated, under which rest the relics of three saints, Ambrogio, Protasio, and Gervasio. The crypt, redesigned in the 18th century with red marble columns, now contains the three silver and crystal urns with the relics.

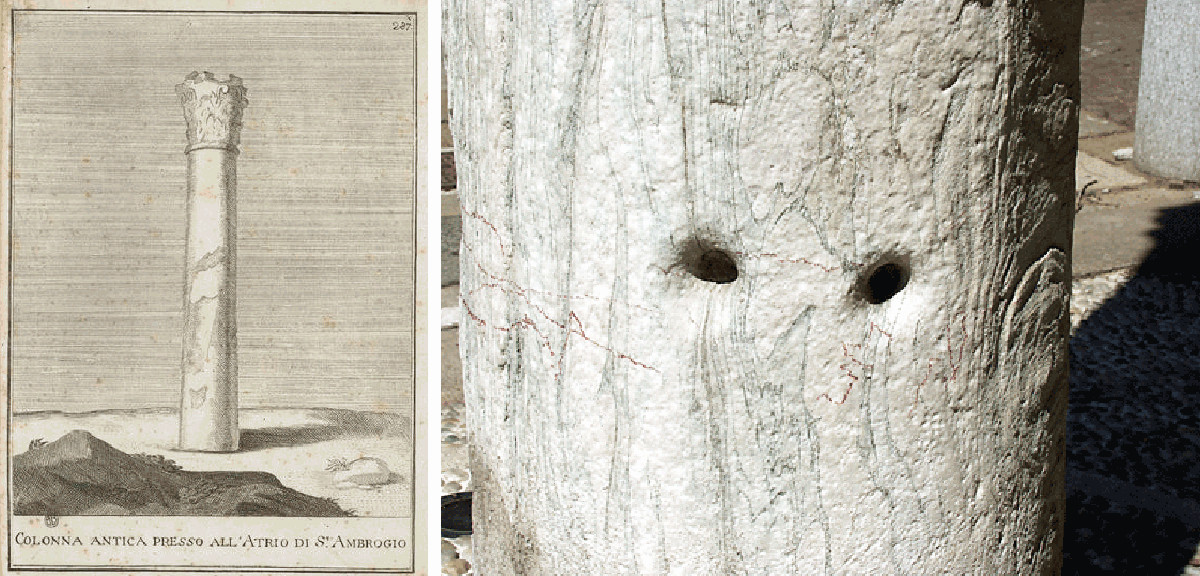

On the same square, Piazza Sant’Ambrogio, the devil’s column can be found. From the looks appears to be a simple Corinth column from the 2nd century with two odd holes at the base. According to the legend the Devil itself released his resentment against the column, violently hitting it with his head, and permanently leaving the imprint of his horns, because he couldn’t get Sant’Ambrogio to follow him to hell. It is tradition for the newly installed Podestà to kiss and hug the column to ensure good luck.

Devil’s Column and its odd imprints.

Walking few meters further, behind the corner, a little shrine can be seen, the Tempio della Vittoria to celebrate Milan’s fallen of the first world war. This octagonal building was opened on the 10th anniversary of the end of the war, every secondary side represents one of the elements: water, fire, water and earth. The admission is free but open only on Wed, Sat and Sun 9:00-12:00 and 13:30-17:00.

Tempio della vittoria, with the inscription on the epistyle “Milanesi caduti in guerra”, Italian for Milanese people fallen in war.

If you’re lucky enough to have a booking for the last supper (12€/7€) or you just would like to see some cloisters, we will walk towards Santa Maria delle Grazie, a UNESCO protected church, after admiring the beautiful decoration of the dome, walk through the door on the left and enter the Bramante’s refined cloisters with the only monochrome fresco of the Virgin Mary, with Christ and the Saints.

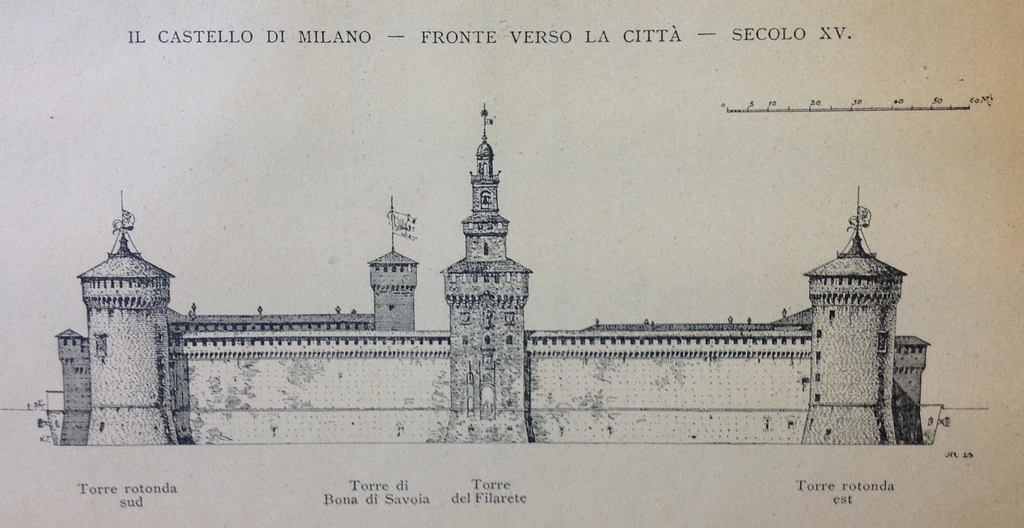

With the last remaining energies we walk to the Castello Sforzesco, named after the Sforza family, that ruled Milan between 1450 and 1535, before the Spanish. Built by Francesco Sforza in the 15th century replacing Castello di Porta Giovia a previous fortification built by the Visconti family on the site of a Roman fortification, Castrum Portae Jovis. The castle was used mostly as a palace from the Sforza family, then it was turned in a proper fortification by the spanish in the 16th century. Left to decay in the 17th and 18th century, it was refurbished by Beltrami in 1893, and it now holds several museums all accessible with a single, cheap, ticket (5€/3€).

The Torre del Filarete, the central tower, exploded in 1521 due to a mishandling of explosives, when it was designated as armoury.

The tower was fully rebuilt only in 1905, and this can be noticed by the different erosion and colour of the bricks.

The original project for the renovation of the Sforza castle by Luca Beltrami.

On the way to our last stop, we cross the Parco Sempione, the biggest park in the city centre, used as parade ground until the foundation of Italy in 1861. On the left site of the park there is the Triennale di Milano, an exhibition center built in 1923 by the fascist regime, that changes periodically and assigns a golden medal every three years to the best artwork displayed.

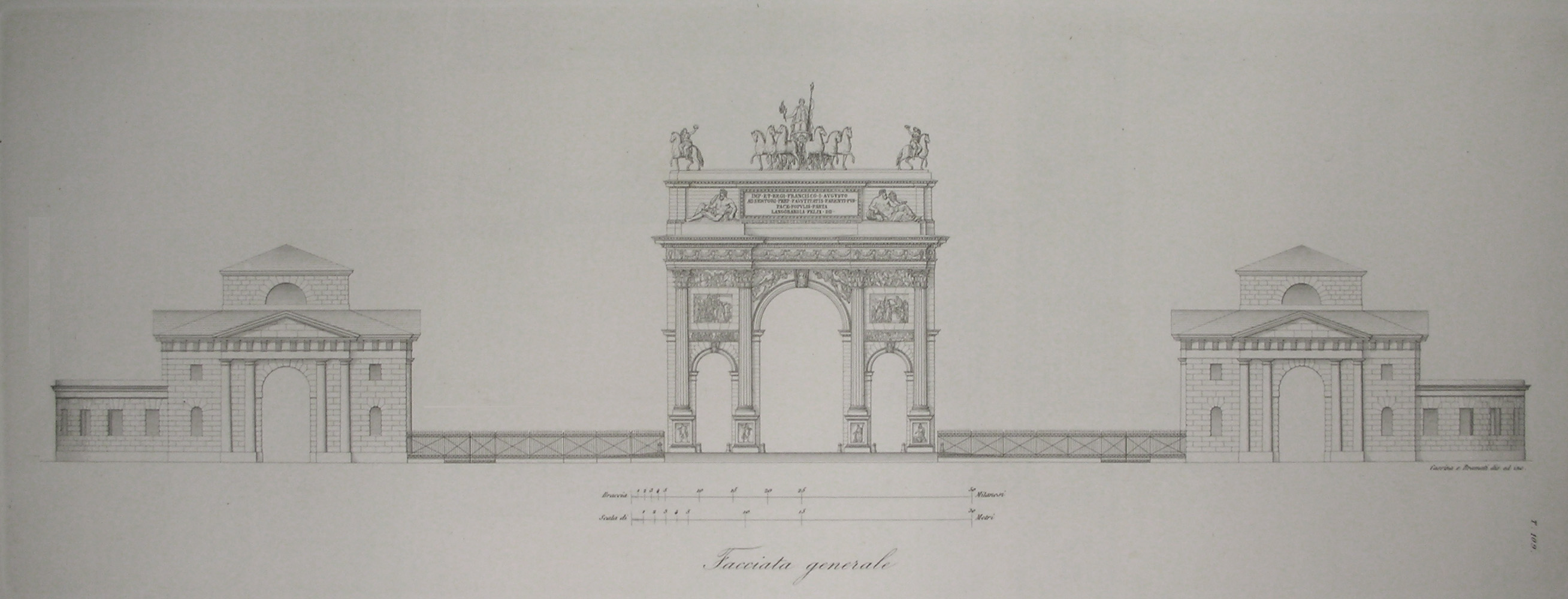

At the other end we find our destination: the Arco della Pace, commissioned by Napoleon’s regime to celebrate the peace was designed in 1807 and interrupted in 1814, to be finished in 1838; with its large size it gives a French/Parisian look to the city. Since at the time Napoleon was already defeated, it was used to celebrate the peace that came with the Restoration and the Congress of Vienna; it was inaugurated with Emperor Ferdinand I. The two tolls on the side are exactly symmetrical and served as a custom office and to delimit the city. A story narrates that a lawyer, reported by his servant, was imprisoned for saying at dinner with friends that the arch was a useless waste of money.

Arco della Pace and its two tolls, illustration by Ferdinando Cassina, 1844.

Our time together sadly ends here today, I hope you enjoyed the walk, and are ready for some rest, after such a long journey through this amazing city, but mostly through time. Some more suggestions will follow, in case you liked this leap in Milan’s history.

Outside of the itinerary, if you happen to pass by the Central Station, other than looking after your belongings because wallets and phones tend to disappear, this fascist-style building is an emblematic monument which isn’t missing stylistic peculiarities. The majestic ticket office is decorated with a polychrome puzzle of different marbles, the elegant déco lamps in the staircase, and the bas reliefs, including the star signs on the sides, are often neglected in the rush of the traveler or commuter.

With a little more time the experience in the station can be changed completely. On the sides of the passageways to the tracks tiled frames depict sceneries from different Italian cities, with no link to the surrounding structure. Another interesting detail can be found on the side of the 23rd track, three lunettes portraying episodes from the history of the Savoy Family, the former Italian royals. Right under these frescos they had a dedicated waiting room, the Sala Reale, finely decorated with paintings depicting war scenes and precious furniture. Today it is open to public only on special occasions, usually a couples of days in spring in occasion of the FAI open museums, and its majesty can’t be admired while waiting for the train. On the floor a swastika motive can be seen, probably due to Adolf Hitler’s visit, and hidden behind a mirror in the toilet there is a no-longer-secret emergency escape, in case anything happened to the royal family. On its right there is a memorial to the fallen rail operators of the first world war.

Inside of the Sala Reale in the central station

The shape of the train hall is common through the whole Europe, due to the exhaust from steam locomotives. The station was built with five arches, 341 meters long, 33,30 meters high, were erected with a crane, leveraging the joints at the base and middle, to make room for a ventilated environment.

This itinerary was first written by Iside Inserrato and me, as an email to friends that asked for a suggestion to visit the city. In the following months it was forwarded to many other people, giving it the need to be rewritten properly, with some specific research and allowing it to have the dignity it deserved. Many thanks go to Lorenzo Malossi, Pietro Mazza, and Francesco Moiana that gave suggestions and helped with the writing process.

Aron Wussler

Map

The GPX can be downloaded here and the detour here

Sources and official websites

T. Livraghi; Milano i luoghi e la storia; Meravigli.

B. Pellegrino; Milano da scoprire; Littleitaly.

A. Lanza, M. Somarè; Milano da scoprire; Idealibri.

L. Beltrami; Relazione di Don Ferrante Gonzaga, governatore di Milano, inviata all’imperatore Carlo V nel 1552 in difesa della progettata cinta dei bastioni; Tipografia Francesco Pagnoni; source.

Maps of the city of Milan.

Villa Necchi Campiglio.

Palazzo Dugnani.

Picture of Piazza San Babila.

Teatro alla Scala.

Palazzo Marino (IT).

Palazzo Marino (EN).

Gallerie d’Italia.

Duomo di Milano.

Picture of the boxers.

Picture of the stained glass in the Duomo.

Fascist architecture in Milan.

Colonne and Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore.

Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio.

Picture of the bronze snake

Picture of the Devil’s Column (I).

Picture of the Devil’s Column (II).

Tempio della vittoria (IT).

Booking tickets for the Last Supper (IT) (yes, only Italian).

Sforza Castle.

Picture of the Sala Reale.